It is Europe’s only place which provides an insight into the culture and history of the ethnic group which moved from Crimea to Lithuania 600 years ago. The Karaite ethnographic exhibition was set up in 1967. It gives visitors a glimpse into the history, customs and everyday life of the Karaites.

The founding of the museum was conceived by Hajji Seraya Khan Shapshal. He was a 19th–20th century scholar, collector, and a well-known public figure of the Karaite community who had an avid interest in the cultures of Eastern nations and especially Karaite culture. In the Karaite congress held in 1927 in Trakai he was elected Karaite community leader and was given the title of Hakhan which is the highest title for a Karaite clergyman. After he assumed this title, Shapshal began collecting items of the spiritual and material heritage of the Karaites and other related nations with an intention to set up a museum. In 1938, his vision came to fruition when the Polish government allocated 33,000 zloty for the construction of a Karaite Museum in Trakai. The construction of the museum was launched under the supervision of architect J. Borovskis and with active involvement of the Karaite community itself. A solemn cornerstone ceremony was held on 6 July 1938. It was attended by government representatives and members of the public from Vilnius and Trakai. However, the construction process was brought to a halt by the outbreak of World War II in 1939 and the whole collection remained in Shapshal’s apartment in Vilnius. The Karaite Museum operated in this manner until the start of 1951.

The same year, the museum was closed and all the exhibits were handed over to the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences and the National Museum of Lithuania. But Shapshal’s dream was meant to be achieved. In 1967, the first Karaite ethnographic exhibition at Trakai History Museum was opened. The exhibition was created on the basis of the collection collected by S. Shapshal. In 2011, a museum was named after S. Shapshal in honour of the 50th anniversary of his death.

Exhibits

The Museum’s exposition includes more than 300 exhibits ranging from an Egyptian Karaite marital agreement through to the collection of Eastern weapons which provide a unique and intimate glimpse into Karaite culture. The exhibition features handicrafts, pieces of clothing, accessories and photographs which shed light on the customs, history and everyday life of the Karaites. The photographs depict Karaites dressed in national costumes.

Visitors will be fascinated by Damascus smoke pipes, a smoking kit (kaljan), a special pot for serving national dishes (tava), a coffee pot, and samples of Karaite national ornaments. After all, the Karaites of Damascus were excellent craftsmen who produced copper items of high artistic value.

The exposition also features a latticework lamp which once decorated the Karaite temple of Damascus before it passed into the hands of the Melkites (Arab Catholics) in 1832, an event after which the Karaite community ceased to exist.

Various household items and room furnishings on display at the museum will also offer a glimpse into the life of the Karaites. Visitors will learn about the Karaite house which was divided into four parts, consisting of the hallway, the kitchen, women’s quarters and men’s quarters. Over time, the men’s quarters became a sitting room. The house was heated using a portable copper heater called mangal. This device was characteristic of a nomadic lifestyle. Family members and guests would sit around the mangal and they would brew coffee in special cups (jibrik).

The exhibits also include two copper pots called kazans. They had both practical and symbolic significance. Gathering around a fireplace or a pot was the symbolic expression of fraternity or kinship for the Turkic peoples. For this reason, such decorative pots were made by master craftsmen.

The exhibition also features an interesting collection of weapons including a leather shield, arrows, a hunting horn, swords (yataghans), and a helmet (shishak).

One of the most interesting exhibits is a wooden cradle which have a long and beautiful history. The cradle called beshik was kept in the women’s room. All the parts of the beshik were fastened using wooden nails. There is a superstition that iron nails should not be used for baby cradles as they are used for making coffins. The rocking of an empty cradle was to be avoided, a superstition held by Crimean Tatars, Kumyks and Turks. The cradle was passed down from generation to generation. It was a great honour for a family to have a cradle inherited from their grandparents or great-grandparents. A baby cradle usually stood on springs. There was an opening in the centre of the bottom in which a clay potty was placed. The mattress also contained an opening to keep the child dry at all times. To prevent the baby from moving around, he or she would be fastened to the cradle using special bandages, and the baby’s legs would be wrapped up separately.

Modern Karaites no longer use beshik cradles thus you can only see one at the museum. This of course is the result of changes in people’s lifestyle brought about by the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Different types of cradles emerged including baby cots, prams and pushchairs, and the tradition of inheriting the cradle from one’s grandparents or great-grandparents has drifted into oblivion.

Immortalizing the memory of Prof. Hajji Seraya Khan Shapshal

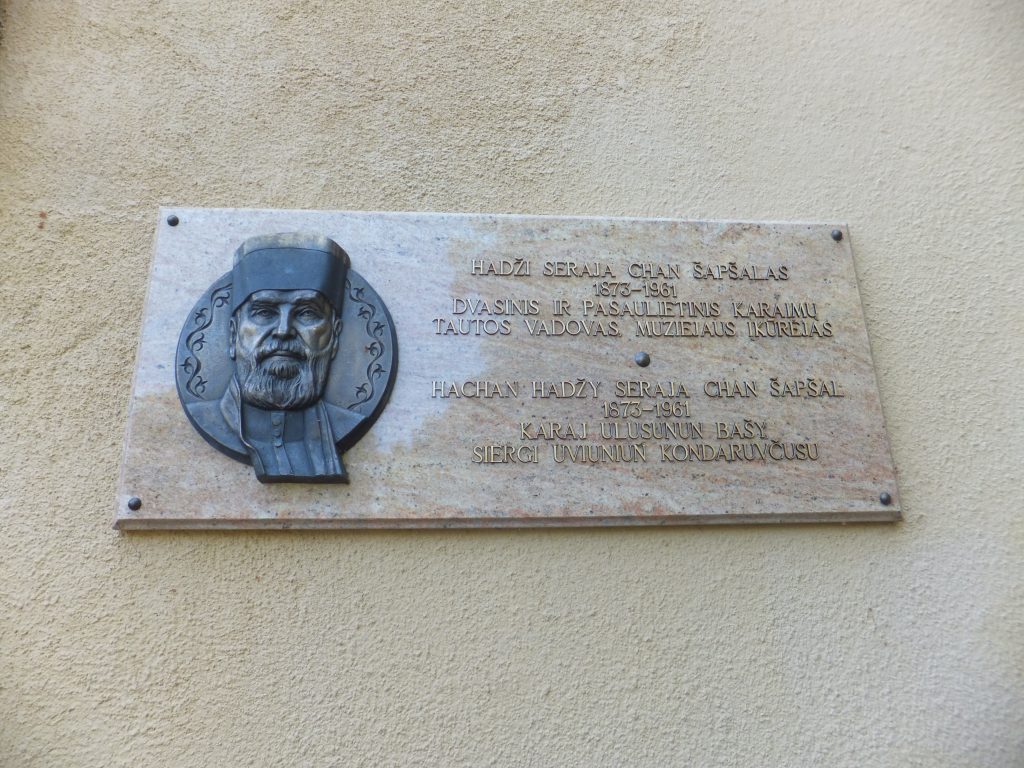

On 28 December 2011, a memorial plaque dedicated to Hajji Seraya Khan Shapshal, a world-famous Orientalist and founder of the Karaite Museum, was unveiled on the present-day building of S. Shapshal Karaite Ethnographic Museum.